Part 1 of our discussion of parapets (Continuity of Control Layers) explored the many reasons continuity of water, air, thermal, and vapor control layers are necessary for long term performance.

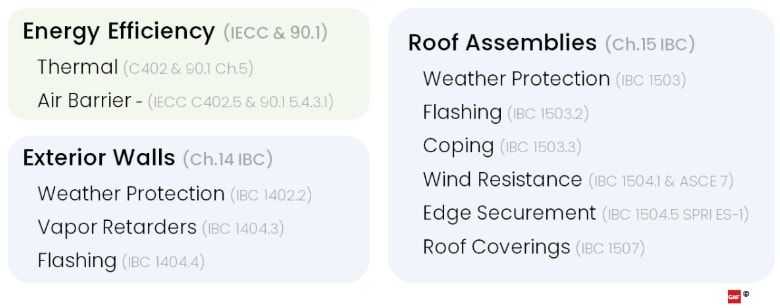

In Part 2, we're discussing the challenges involved in navigating the range of national model codes and standards that will influence your design. Codes under discussion include the 2018 International Building Code (IBC), the 2018 International Energy Efficiency Code (IECC), and the ANSI/ASHRAE/IES Standard 90.1-2016 (ASHRAE 90.1).

The summary provided in this article is not intended to be an exhaustive list of requirements for exterior wall and roof systems in the referenced national model building and energy codes. Different versions of the referenced codes have additional and/or different requirements; these requirements may also vary by adoption and modification by the local authority having jurisdiction. It is important to refer to local codes for the applicable requirements.

The requirements for parapets generally come from the building code (IBC) and the energy code (IECC and ASHRAE 90.1). The requirements within the building and energy codes can be mandated prescriptively, as a performance threshold, or by reference through specific key standards. The performance standards are important because they don't attempt to regulate by providing exhaustive lists and itemized component requirements, like a prescriptive method. These performance requirements establish the design benchmark and then provide a methodology to demonstrate compliance with the benchmark.

The building codes and standards do not always address parapets exclusively, but many refer to "Exterior Walls" separately from "Roof Assemblies".

Summarized applicable code references for parapets.

Exterior Walls in the Building Code

The exterior wall requirements for parapets are covered in Chapter 14 of the IBC which addresses "exterior walls, wall coverings, & components." For parapets, the requirements for weather protection, water-resistive barriers (WRBs), managing vapor, and flashing apply as they do for the rest of the exterior building walls.

IBC Chapter 14: Exterior Wall applicable area highlighted in blue.

Exterior Wall Flashing

Flashing is very important and is generally repeated in both the wall (IBC 1404.4) and roof provisions of the code. The IBC includes the principle that "flashing shall be installed… to prevent moisture from entering the wall or to redirect that moisture to the exterior." This is an important starting point for parapet design where the sequencing can be a challenge among numerous wall- and roof-system contractors.

While not an exhaustive list, IBC 1404.4 includes a minimum list of areas requiring exterior wall flashing. These are summarized below:

- Penetrations and terminations

- Intersections with roofs, chimneys, porches, decks, balconies and similar projections

- Built-in gutters and similar locations where moisture could enter the wall

- Flashing with projecting flanges, installed on both sides and the ends of copings

At all of the prescriptive flashing locations listed in the IBC, the purpose is two-fold. The first is for the flashing to be installed in a way that prevents water from entering the wall system. This concept is known as "shingle fashion," or installing components of the roof, exterior wall, and parapet "such that upper layers of material are placed overlapping lower layers of material to provide for drainage via gravity and moisture control" (IBC 202). Logistically, this is best accomplished onsite by applying materials from the bottom of the building to the top, so the next progressive layer or system is then lapped correctly.

The second, and more challenging flashing requirement, is to also be installed in a manner that permits water to exit the wall system if it enters incidentally. This requires the parapet to be designed with a method and pathway for water to drain from the flashing, even from behind the cladding (think weep holes at masonry shelf angles). In addition to providing a means for drainage, the IBC also includes a drainage scenario to avoid exterior wall pockets (1404.4.1). Wall pockets or crevices are locations within a wall assembly "in which moisture can accumulate." These scenarios can be common in parapets where the exterior wall, roof, and parapet wall above might not always be in alignment. In parapets, these wall pockets should be avoided or protected with appropriate flashing for the application.

Exterior Wall Weather Protection

The Weather protection section (IBC 1402.2) requires that the exterior wall "shall be designed and constructed in such a manner as to prevent the accumulation of water within the wall assembly". One of the methods prescribed in this section is to include a secondary water management layer, or "water-resistive barrier" (WRB), behind the exterior cladding in the exterior wall portion of a parapet. Beyond including the WRB layer, "a means for draining water that enters the assembly to the exterior" must also be provided in the parapet wall design. There are exceptions to the secondary WRB and drainage requirements provided in the IBC for concrete and specifically tested systems, but the benefits for designed water control is applicable for all construction types.

Exterior Wall Vapor Retarders

In exterior parapet walls, protection against condensation is also required to be compliant with the vapor retarders portion (IBC 1404.3). Vapor retarder materials are separated into three classes by ASTM E96 testing (Procedure A, desiccant method):

- Class I: 0.1 perm or less;

- Class II: 0.1 < perm="" ≤="" 1.0="">

- Class III: 1.0 < perm="" ≤="" 10="">

The vapor retarder classes are referenced in the IBC to identify by climate zone if a material is permitted in the assembly in a prescriptive manner (IBC 1404.3.1 and 1404.3.2). It is important to note that all materials have vapor retarding properties to some degree and may limit vapor transmission without the addition of a dedicated vapor control layer. This is also why the IBC includes the alternate performance compliance of providing a "design using accepted engineering practice for hygrothermal analysis" as described in the initial language of 1404.3.

In most cases, if a vapor control layer is needed, it is a good idea to select a vapor retarder that will allow some amount of drying from diffusion. High-humidity interior environments such as natatoriums, manufacturing facilities, and grow houses may require a vapor barrier for long-term performance. However, the decision of whether or not to add a vapor control layer to a roof assembly is normally based on risk and is best made with a building enclosure consultant. The weather protection and vapor retarding sections of the IBC apply to exterior walls, but parapets may have very different design and performance requirements than the wall assembly below the roof. That is why it is important to maintain continuity of the four control layers at this interface.

Roof Assemblies in the Building Code

The roofing portion for parapets is covered in Chapter 15 of the IBC which addresses Roof assemblies, specifically the "design, materials, construction and quality" of roofs. Regarding parapets, the roof system requirements impact the wall where terminations and transitions occur. The requirements include weather protection, flashing, coping, wind resistance design, edge securement, and specific requirements for various types of roof coverings.

IBC Chapter 15: Roof Assembly applicable area highlighted in blue.

Roof Assembly Weather Protection

The requirements for weather protection (IBC 1503) are fairly broad, requiring roof decks covered with approved roof coverings. Much more detail is covered in the additional IBC sections regarding roofing and parapets. In the roofing provisions, it is important to note that compliance with "the manufacturer's approved instructions" doesn't just affect a project's eligibility for warranty, but is also required for building code compliance.

Roof Assembly Flashing

The requirements for flashing (IBC 1503.2) are repeated in part across the wall and roof portions of the code. This repetition highlights the importance of managing water control at the transitions. The code requirements for both roofs and walls support the water control layer principles in the pen test discussed previously. The roofing chapter in the code also directly mentions the parapet walls as a critical location for both roof system transition flashing and requirements for copings. While not an exhaustive list, IBC 1503.2 includes a minimum list of areas requiring roof flashing. These are summarized below:

- Flashing joints in copings

- At moisture-permeable materials

- At intersections with parapet walls

- At other penetrations through the roof plane

Roof Assembly Coping

The roof requirements for parapet wall copings are spread across many categories. One section specific to copings (IBC 1503.3) has a limited scope, requiring materials to be limited to "noncombustible, weatherproof materials" and be installed with a "width not less than the thickness of the parapet wall". Many other requirements in the code also apply to copings in the code, such as flashing, wind design loads, and edge securement performance. More will be discussed about copings in those sections.

Roof Wind Resistance

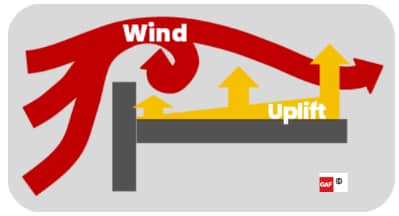

The wind resistance for low-slope commercial roof decks and roof coverings (IBC 1504.1) is required to be designed in accordance with IBC 1609.5, which ultimately leads to utilizing ASCE 7 for determining design wind loads. There are numerous updates to ASCE 7 – 2005, 2010, or 2016 – and each has its own nuance as to how it impacts roof design loads. Because ASCE 7 is a performance standard, it is possible to use a version with higher performance requirements because designs do not need to be the minimum allowance. Parapets are a combination of wall and roof pressures. The exact height of the parapet is not factored into the roof wind uplift calculations, but if the parapet is 3' or higher, the perimeter values can be used at the corners, lowering the uplift requirements for that portion of the roof area.

Parapets can help reduce wind uplift at the corners and perimeter

Roof Edge Securement

Securing the edges on low-slope roofs (IBC 1504.5) has a significant impact on preventing failure and allowing the roof system to resist loads as it was designed. In addition to designing the wind resistance performance for the entire building (i.e., walls, roofs, and parapets) per ASCE 7, metal roof edges are required to be tested for resistance in accordance with Test Methods RE-1, RE-2 and RE-3 of ANSI/SPRI ES-1. The referenced standard ANSI/SPRI ES-1 is a performance requirement that is specific to the strength of metal roof edges (more here about roof edge performance compliance). ES-1 covers the "baseline" flush roof edge as well as parapet coping caps. When designing, it is important to specify compliance with ES-1 in the construction documents.

Roof Coverings

The IBC provides minimum installation criteria (IBC 1507) for various roof systems, based specifically on the attributes of that roof covering. In addition to the prescriptive criteria listed within, the IBC also mandates that "Roof coverings shall be applied in accordance with the… manufacturer's installation instructions." Generally, the content of these roof covering sections address minimum substrate requirements, minimum roof slope, ballast requirements, and relative ASTM references to material standards, such as D6878 Standard Specification for Thermoplastic Polyolefin (TPO) Based Sheet Roofing.

Energy Efficiency for Parapets

Generally, within the IBC it is required that a building be "designed and constructed in accordance with the International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) 1301.1.1". The IECC has both residential and commercial provisions, and the commercial provisions apply to "all buildings except for residential buildings 3 stories or less in height." The IECC is structured in a way that provides the option of either complying with the prescriptive requirements within it or by complying with the alternate ASHRAE 90.1 energy standard.

Compliance Alternatives

The IECC has multiple compliance paths within it, including:

- Either following the prescriptive requirements within the IECC or ASHRAE 90.1, or

- Following the performance modeling requirements of ASHRAE 90.1 Appendix G.

The prescriptive options within both the IECC and the reference standard ASHRAE 90.1 primarily regulate energy use by providing lists and itemized requirements. These can be helpful when the building is straightforward and tradeoffs don't need to be made. When a building is more complex, has specific energy usage demands, or if an owner wants to demonstrate energy compliance beyond code, the performance path within ASHRAE 90.1 Appendix G is the methodology required. For example, any modeling being performed to show compliance with LEED is being performed to comply with Appendix G in ASHRAE 90.1. A growing method of compliance is whole-building design energy modeling and onsite performance testing happening in new construction. When an existing building is reroofed, the designer will most likely follow the prescriptive path to determine the amount of insulation to use.

Insulation

The insulation requirements in the table include both cavity and continuous insulation, but vary based on the framing material (IECC C301.1 & 90.1 Annex 1). Including continuous insulation in both the walls and roof systems of the parapet helps manage thermal bridging across the assemblies. The prescriptive tables in the energy codes dictate minimum R-Values in the roofs and walls based on the climate zone of the project site, the building use, and the framing materials of the wall and roof system. As described earlier in the thermal control discussion, the framing materials matter in the prescriptive requirements, especially when insulation is placed between framing members in parapet cavities.

For more complex details like a parapet, the energy code doesn't get into separate requirements for the insulation. The codes generally require that continuous insulation be depicted in the construction documents with sufficient clarity to indicate the location, extent of the work, and show sufficient detail for continuity of the thermal control layer. Per the IECC (C103.2), insulation continuity for complex conditions should be shown in the details.

Air Barrier

ASHRAE 90.1 defines a Continuous Air Barrier as a "combination of interconnected materials, assemblies, and sealed joints and components which together minimize air leakage into or out of the building envelope." It's a good definition and an accurate description of what is needed to have a completed building enclosure that minimizes air leakage (IECC C402.5 & 90.1 5.4.3.1). Actual air leakage for a building is measured by pressurizing the enclosure with a set of blowers and measuring the airflow through the blowers to determine the air leakage through the enclosure being tested, on all 6 sides. Materials and assemblies used as a part of the building's continuous air barrier are generally tested by the manufacturers of those materials and systems to comply when installed in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions for that application.

The ultimate goal of airtightness is whole-building performance. To help accomplish that goal, the energy code also specifies aspects of air barrier design (IECC C103.2 & 90.1 5.4.3.1.1) and installation (IECC C402.5.1.1 & 90.1 5.4.3.1.2) for continuity across joints, penetrations, and assemblies. Below is a brief summary of the design and installation requirements from ASHRAE 90.1:

- Air Barrier Design

- Components, Joints and Penetrations details

- Extending over all surfaces, including the roof

- Resist pressures from wind, mechanical, stack effect

- Air Barrier Installation

- Junctions between walls and roofs or ceilings

- Penetrations at roofs, walls, and floors

- Joints, seams, and connections between planes

- In accordance with the manufacturer's instructions

Code Summary

For the various applicable codes and standards, in both roofs and walls, weather protection and flashing are important requirements at all transitions and penetrations, including parapet conditions. It is vital to specify key reference standards for wind and edge securement, in order to achieve the performance needed to keep the roof on the building as intended.

In general, the energy codes require continuity of the thermal and air control layers. Detailing the thermal control and air barriers to be continuous in the design AND field installation are critical for energy code compliance.

For more information on parapet and control layer continuity, register for the Continuing Education Center webinar, Parapet Predicaments and Roof Edge Conundrums, sponsored by GAF and presented by Jennifer Keegan, AAIA and Benjamin Meyer, AIA, LEED AP.

For more information on parapet and control layer continuity, read the Continuing Education Center article, Parapets—Continuity of Control Layers, sponsored by GAF and written by Benjamin Meyer, AIA, LEED AP.